I hoped to be able to announce today that the paperback version of my boxset, Hannah’s Lieutenant, is available. Unfortunately, I ran into a snag with Amazon. They want me to bill it as a single, not as a boxset—perhaps because I gave it a whole new name which I found more descriptive than just merely describing it as a boxset of the two included titles, Hannah’s Handkerchief and Hannah’s Highest Regard—the two books originally published in 2020. Because together they told Hannah’s story, I wanted to combine them for the print version. If you have not yet read Hannah’s story in ebook format and prefer print, keep an eye out. I will get it in print, just not today.

In 2020, I spent a lot of time researching and writing about the Kansas frontier—not only for my two Hannah books, but for the three books I wrote for the Widows, Brides, & Secret Babies series. In honor of this project, all I can say is, “I’m b-a-a-a-ck!” My writing connection will become more evident once I share where my first original publication for 2022 will be set.

One of the frustrating aspects of researching frontier forts is that there were often several military camps, cantonments, posts, and forts in the same general area, all with different names. However, it is the primitive nature of the forts as they existed in 1865 at the start of Hannah’s story that I wish to discuss.

Fort Ellsworth

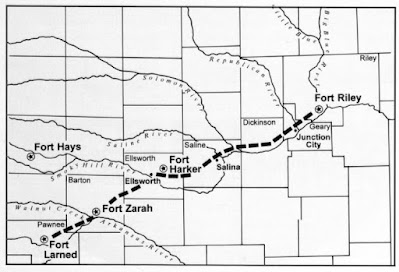

Built along the Smoky Hill River and Smoky Hill Trail, Fort Ellsworth served to protect the military road that ran from there to Fort Zarah located along the Santa Fe Trail near the big bend in the Arkansas River.

The camp occupied the same general site as a stagecoach station and a hunting and trading ranch. It was also the point where the Fort Riley-Fort Larned Road crossed the Smokey Hill River in the present Ellsworth County in Kansas.

Daniel Page and Joseph Lehman established the hunting camp and trading ranch in 1860. The men gathered wolf and buffalo hides for trade. In 1862 the ranch became a station for the Kansas Stage Company. The station kept and fed mules that were changed when stagecoaches came through. The station was raided by Confederate soldiers in September of that year.

In August 1864, Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, the department commander, established a military camp four miles southeast of the stage and hunting ranch site. The fort's mission was to protect the area settlers from hostile Indians. Soldiers from the 7th Iowa Cavalry, under the command of 2nd Lt. Allen Ellsworth, set up the fort. They built a two-story blockhouse using logs already cut and hewn on two sides found at the abandoned Page-Lehman ranch. The blockhouse became the nucleus of the fort. Other than that, since the fort was intended to be temporary, it consisted of hastily-constructed dugouts and log structures, which served as quarters for the soldiers. Other structures included a commissary, an officers' mess, and a makeshift shelter for the horses. Based on the descriptions, all of these structures were made largely from materials on hand--logs, sod, and brush. Maj. Gen. Curtis named the post Fort Ellsworth for Lt. Ellsworth.

Even though some buildings were constructed by the end of the Civil War, the men still lived in primitive housing. M. Wisner wrote his company arrived in January 1865 and had to build dugouts with mud chimneys. He also noted these dugouts were comfortable in the severe cold weather.

That changed in 1866 when it was decided to abandon the fort at its location along the Smoky Hill River. 1867, a new fort, Fort Harker, was built about a mile to the northeast. If you wish to read my 2020 post on another blog about Forts Ellsworth and Harker, please CLICK HERE.

Fort Larned

I do not have pictures of the dugouts at Fort Ellsworth. However, they were probably fairly similar to those built at Fort Larned, shown above, when it was first established in October 22, 1859

William Bent, agent for the Upper Arkansas Indians, in a letter to A. M. Robinson, superintendent of Indian affairs for the Central Superintendency at St. Louis, reported he had encountered 2,500 Kiowa and Comanche warriors at the mouth of Walnut creek (25 miles east of Pawnee Fork). Bent also stated that he had witnessed, to October of 1859, 60,000 white people along the trail, which he attributed the accelerated traffic to the discovery of gold in the Pike's Peak region. His report pointed out the difficulty the Indians were having to maintain their natural subsistence. There was also the need to protect the recently established stage stations on the Trail from the resistance of the Plains Indians. He suggested the location of the fort.

The exact location of this installation was at the base of Lookout Hill (now known as Jenkins Hill), on the south side of the Pawnee, eight miles from its confluence with the Arkansas River.

A description of the first structures of "Camp on the Pawnee Fork" is given in Capt. Lambert Wolf's diary:

October 23, plans are made for the horse and cattle stable, also for officers' and company quarters, all of which are to be built of sod, cut with spades by members of our company. Our stable [probably meaning fortification] is to be 100 feet square . . . wall 12 feet high . . . .

These plans must have been set aside for several months. As late as July 22, 1860, a letter from Camp Alert (as the installation was then called), failed to note anything more permanent than tents in the fort.

The forces of Stewart and Wessels remained at "Camp on the Pawnee Fork" until November 27, 1859, when they were relieved by a detail of 40 men under the command of one Lieutenant Bell, whose specific instructions were to act as a construction crew for the permanent site.

Fort Larned brick officers' quarters built in 1868

The first buildings were constructed of adobe bricks, which, although an improvement over tents and dugouts, were subject to bug infestation and water damage during heavy rains. Plans to build more solid structures of nearby native stone was put on hold due to the Civil War. The fort made do with its adobe buildings until 1866. It was these years immediately following the American Civil War in which Quartermaster Jake Burdock arrives at Fort Larned.

You might wish to read my earlier post about Fort Larned on another blog for which I write. Please CLICK HERE.

Originally built to protect the Butterfield Overland Despatch line that tended to follow the Smoky Hills River, the original Fort Hays was destroyed by a flood—common occurrences along the rivers of the Kansas frontier—in June of 1867. Nine soldiers and civilians died. This forced the relocation of the fort.

By this time, the army wanted the fort to be used as a supply depot for other forts in the area, this provided the momentum to relocate the fort close to the railroad line several miles away. Two weeks later, on June 23, the new Fort Hays was built and occupied fifteen miles west of the previous location and near the railroad right-of-way.

You might wish to learn more about the old and new Fort Hays and its role as a large supply depot to service forts to the south and west by reading my 2020 post on another blog. Please CLICK HERE.

Fort Zarah

On June 14, 1864, Maj. T. I. McKenny, inspector-general and his party were en route to Fort Larned escorting a mail stage. After a 40-mile journey from Smoky Hill crossing, the site of early Fort Ellsworth where construction on a blockout was underway, they reached Walnut Creek. According to his report, he "camped at a point where the road intersects the old Santa Fe road, and where the Leavenworth and Kansas City mails are due at the same time"; "found the ranch [Rath's] entirely deserted." (He saw the owner next day at Fort Larned.)

In his June 15 report, written at Fort Larned, Major McKenny included his intent to "build a block-house" at Walnut Creek on his return trip. Camp Dunlap was established two miles east of present-day Great Bend in July 1864. The major left Captain Dunlap with 45 men, Fifteenth Kansas there. Initially, it was comprised of dugouts and tents, but the men were left to build a stone fort.

You might want to read more details about Fort Zarah from of my earlier blog posts on a different blog. Please CLICK HERE.

Fort Dodge

The Kansas fort at the greatest distance from Fort Riley, the primary supply fort for Kansas and forts farther west and south, was Fort Dodge. It was located east of the western junction of the wet and dry routes of the Santa Fe Trail. This fort was originally a campground along the portion of the Santa Fe Trail that followed the Arkansas River.

On March 23, 1865, Major General Grenville M. Dodge, commander of the 11th and 16th Kansas Cavalry Regiments, proposed establishing a new military post west of Fort Larned. On April 10, 1865, Captain Henry Pearce, with Company C, Eleventh Cavalry Regiment, and Company F, Second U.S. Volunteer Infantry (better known as “galvanized Yankees”—Confederate prisoners-of-war who chose to join the Union Army to serve on the frontier rather than languish and probably die in prisoner-of-war camps.) traveled from Fort Larned to occupy and establish Fort Dodge.

In the beginning, Fort Dodge was a primitive affair. Like other forts built along rivers with steep banks and a scarcity of timber, housing was created by cutting into the dirt banks. One source claims the housing was dug along the south side of the river and covered with canvas roofs.

Another source—the one I relied upon in my Hannah books—claimed the initial buildings were earth dugouts excavated along the north bank of the Arkansas River. With no lumber or hardware, the men used grass and earth—the materials available in the area—to create the seventy sod dugouts that were 10 X 12 feet in circumference and seven feet deep. A door to the south faced the river and a hole in the roof admitted air and light. Their one redeeming value was that the dirt walls provided insulation, keeping the soldiers warm in winter and cooler in the prairie summer heat.

Banks of earth were bunks for the soddies that slept from two to four men. All was good until the Arkansas River flooded, which sent the soldiers scrambling to save as many of their possessions as possible before they fled to higher ground.

Sanitation was poor. Pneumonia, dysentery, diarrhea, and

malaria were common in the first year in the isolated fort.

This was how I described Fort Dodge where my hero, First Lieutenant Jake Burdock, in Hannah’s Handkerchief, now the first book in my Hannah’s Lieutenant boxset, expected to stay when he was sent there to assess the needs of the fort as part of his duties of quartermaster assigned to the forts on the Kansas Frontier. Here is an excerpt from a letter from his letter to Hannah:

… However, my concerns revolve around the quarters I have heard they are reduced to inhabiting that I suspect are unacceptable. With no wood within fifteen miles of the fort’s location, caves have been dug into the banks of the Arkansas River, similar to the Fort Ellsworth dugouts along the banks of the Smoky Hill River. They contain one opening for an entry and another on top for light and smoke to escape, all where rain and the rising river can weaken the soil, which leads to collapse. Although I have been assured such quarters will insulate and protect them from the worst of the winter storms that sweep across the plains, I suspect such living conditions, where they burrow into the earth like prairie dogs, are not adequate, not even for galvanized Yankees. Besides, that unit is due to be mustered out shortly.

Who knows but what I might find myself wintering in such conditions and might soon be grateful for my earthen habitat? If such is the case, I will let you know how I fare….

After reading this letter to her father, here is part of the conversation between them:

… By the way her father’s voice caught when he paused, Hannah suspected he had more to say on the subject.

“Your mother told me about the talk you two had about soddies, about how you don’t want to marry a farmer if it means living in one.”

Even though she knew her face was hidden from her father by the darkness, Hannah felt herself blush. “I figured she would. It’s true. People might accuse me of being proud and too particular, but I would much rather live in a house that is not made of dirt.”

1879 Kansas Sod House

“It sounds like, before the year’s out, your soldier might be living in something like a soddie, only not as well-constructed as the ones built around here. Would you be willing to marry an officer if officers’ quarters were in a dirt cave?”

Hannah turned her head aside. “I can’t say that prospect appeals to me.”…

Between the two books, Hannah

ends up being courted by two different Army lieutenants. Which will she choose?

I’ll let you read the book to find out. However, here is one clue regarding the

home in which she will eventually end up living:

You may find my boxset, Hannah’s Lieutenant, including the book description, by CLICKING HERE.

I mentioned at the top that I was back in Kansas for my first book in 2022. I do not have a book link for it yet, but along with my book description, I will share it on my NEWSLETTER this coming Friday, January 14, 2022. What I will do is leave you with a few teasers:

The book takes place in 1871, three years after Hannah’s Lieutenant ends.

I traded stagecoaches and freight wagons for railroad lines.

I traded forts and stagecoach stations for a cow town and stockyards.

Sources:

https://kshs.org/kansapedia/fort-ellsworth/17158

https://www.santafetrailresearch.com/spacepix/fort-ellsworth.html

https://www.santafetrailresearch.com/research/fort-larned.html

https://www.kshs.org/p/the-story-of-fort-larned/13139

George A. Root. ed., "Extracts From the Diary of Captain Lambert Bowman Wolf," The Kansas Historical Quarterly, Topeka, v. 1 (1931 - 1932), p. 204.

Lee, Wayne C. and Howard C. Raynesford; Trails of the Smoky Hill

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ks-fortdodge/

https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/housing-in-kansas-history/15143

Wikipedia

No comments:

Post a Comment