When travelers heading west were faced with a four- or five-month journey, knowing the location of a midpoint was reassuring. Depending on where the group originated, the roughly 2,000 mile trip began from three main starting points along the Missouri River (St. Joseph or Independence, Missouri, and Omaha, Nebraska). The first version of the trail had been established by fur trappers and traders and was navigated on foot or by horseback. As the years passed, the trail was widened and made accessible by wagons. In 1836, Marcus Whitman and Henry Spalding set out with their wives and others to establish a mission in Washington Territory. They traveled from Independence, Missouri, and reached Fort Hall in current-day Idaho. From that location, they traveled the rest of the way on pack mules. The trail was developed farther west in subsequent years, and alternate trails to California, Montana, and Utah split off from the main one that ended in Oregon City, Oregon.

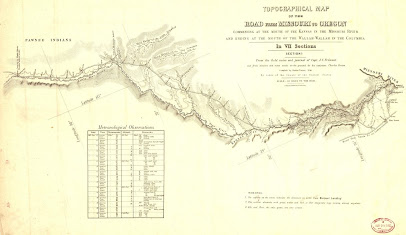

The earliest travelers like those on the Great Migration of 1843 (which included more than 700 people) headed out with a destination of Oregon with few resources to guide them. By 1848, a map drawn by John C. Fremont of the U.S. Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers based on several trips he made from 1842-1846 provided a clear route. the map is so detailed (even included meteorological data) was printed in seven sections. Hiring a guide for the journey became important to achieve the best success for the group.

Either by word of mouth or on the expertise of the guides, Independence Rock in central Wyoming (about 60 miles SW of Casper) was recognized as the spot to reach by the Fourth of July to avoid encountering snow in the westerly mountains that needed to be crossed. The isolated peak of granite rock stands 130 feet high above the surrounding prairie and is 1,900 feet long and 850 feet wide. Because of its prominence, it could be seen on the horizon for multiple days. Travelers often rested near the rock and celebrated before continuing the trek. Many signed their names using carving tools or with a mixture of ash and grease. As early as 1840, it was called the Register of the Desert by an early explorer and missionary.

|

| Independence Rock, 1870 from US Geological Survey |

John C. Fremont camped near the rock in August 1843 and carved a large cross on it. He wrote in his journal about the famous names he recognized inscribed on the surface. A traveling party in 1847 blasted the cross from the rock, seeing it as a representation of the Pope and Catholicism. (Fremont was actually an Episcopalian.) Both of these facts about Fremont’s connection to the Oregon Trail I found fascinating and included them in my latest wagon train story, Tilda, book 31 of the Prairie Roses Collection multi-author series.

Following her parents’ death, Tilda Torsdotter leaves Illinois with her cousin’s family to head to California. After cousin Rakel dies, Albert looks to Tilda to fulfill her cousin’s duties--all of them. She’s trapped.

Hiring on as

a driver on a wagon train seems like the easiest way for Flynn Mannix to reach

western America. Until he witnesses an inappropriate encounter and steps in.

Suddenly, he’s committed to a marriage of convenience with Tilda and

responsible for her safety until they reach California. At the end of the

trail, will the couple go their separate ways, or will they realize the

experience has made their marriage real?

No comments:

Post a Comment